Paper Money in Early New South Wales

By AG | Tuesday, 13 September 2011

In the first few years of the newly founded colony of New South Wales, the need for money as a medium of exchange was not great. Survival was foremost in the minds of the the administrators, the soldiers of the New South Wales Corps and the convicts. Drought, food shortages, a lack of accommodation and the challenge of adapting to a new land and climate were far more important than any concerns about a minor nuisance such as a lack of ready money.

By the mid-1790's, the drought had eased and crop harvests were sufficient to feed the population. The colony's future was safe. By then, along with the convict transport fleets, a steady trickle of free settlers began to arrive. Three separate groups emerged - the convicts and their administrators, the producers (farmers and tradesmen) and the merchants (storekeepers and traders). Each group could be of benefit to the others, only if suitable mediums of exchange could be established.

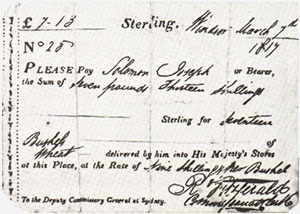

The Government Store, known as the Commissariat, was a logical starting point. In return for goods and produce, the Commissariat issued Store Receipts which showed the producers name, the type and quantity of goods delivered and the price paid. These receipts were to be redeemed periodically for Bills of Exchange on the Treasury in England - the redemption dates were fixed by the authorities.

Although not intended for general circulation, store receipts were negotiable and quickly gained acceptance as a medium of exchange. A local producer had two choices. The first was to save up the store receipts, consolidate them for a Bill on the English Treasury, and forward the Bill to England to create a credit which could be used to purchase supplies - a process spanning several months, often more than a year.

The second choice was more immediate. The store receipt could be taken to a merchant and used to obtain supplies locally. Any unused balance could be paid by the merchant in the form of a private currency/promissory note or retained as a credit. A shortage of coins usually prevented change being given in specie. The merchant, over time, acquired a number of these transferable store receipts and could either consolidate them or use them to replenish stocks locally. A cycle of circulation was thus created.

Small transactions, such as the purchase of a loaf of bread (around 9 pence in the early 1800's) presented a problem which was overcome by the use of small denomination, private currency notes. These notes were issued by reputable individuals and businesses and were used in the same way as banknotes are used today. As more small denomination coins became available, the authorities gradually increased the minimum value for which private currency notes could be issued.

There were other sources of paper money which circulated in the colony. Banknotes and bills from England and Ireland were utilised. Cheques were a very important part of commerce, being used for a large proportion of currency transactions (there are reports that at times, 9 out of 10 transactions were settled by private of bank cheque. In 19th century Australia, the use of hand-written and printed cheques, per head of population, was one of the highest in the world.

As the colony expanded, additional Commissariat offices were opened at Parramatta, Liverpool, Windsor, Bathurst, Newcastle, Hobart Town and Port Dalrymple - the last two in Van Diemen's Land. The transfer of funds over long distances within the colony was enabled by Bills of Exchange drawn on the issuing Commissariat office (not on the English Treasury).

To pay the soldiers of the New South Wales Corps, and to pay for supplies, military commanders issued Paymaster's Notes. Debts incurred by the regiment were paid for using promissory notes with a variable, handwritten value while the soldiers were paid with fixed denomination currency notes. These notes circulated in the same way as Commissariat store receipts and were consolidated quarterly for bills on either the English Treasury or the London agent of the regiment. Naval vessels visiting the colony also issued military paymaster's notes for their supplies. These were consolidated for bills on the Commissioners for Victualling His Majesty's Navy.

In 1810, Governor Macquarie established the Colonial Police Fund - the forerunner of a Colonial Treasury. Funds were received from fines, licenses, harbour dues, rentals, duties, etc., and were used to pay for public works - roads, bridges, etc., - which lay outside the penal administration's responsibility. Fixed value Police Fund Notes joined the varied list of circulating paper money used in the colony.

The issue of Commissariat store receipts was suspended for two periods. Between July, 1813 and March, 1815, Deputy Commissary General Allan issued his own private, fixed value promissory (currency) notes. Under this system, the notes were paid directly to the producer and Allan fully recouped their value from the government. There was no intermediate use of a receipt document. Governor Macquarie stopped the practice when it became clear that Allen was the main beneficiary whenever a note was lost or destroyed and thus was not later consolidated.

Between February, 1819 and June, 1820, Deputy Commissary General Drennan implemented a non-transferable type of store receipt which could be redeemed for Private Commissariat Currency Notes. Problems in travelling to a location where the non-negotiable receipts could be consolidated and suspect accounting practices in dealing with cancelled and lost receipts saw Drennan removed from office. He was later sent back to England, under arrest. The system of transferable store receipts was reinstated with some improvements to stop their theft and forgery.

The vast majority of commercial transactions conducted within the colony in the early decades had come to depend on a complex system of credit. While far from ideal, nevertheless the system worked. Commissariat store receipts, bills of exchange on the English Treasury and other government offices, Police Fund notes, private promissary notes, commissariat currency notes, Paymasters bills and notes, and banknotes from England and Ireland all played their part in a system of exchange which was plagued by a lack of hard currency - specie.

Improvements in the situation were slow. The introduction of banking establishments (the first being the Bank of New South Wales in 1817) and an improved flow of English coins in the second half of the 1820's gradually eased the almost total reliance on non-traditional mediums of exchange which had been forced to make do.

As the number of banking establishments grew, so to did the number and variety of banknote issues. The gold rushes of the 1850's saw the number of circulating banknotes increase enormously. Every person who accepted a note from a bank in exchange for gold or sovereigns was effectively lodging an interest free deposit. The banks' only expenses were the costs of engraving and printing the notes. Although they had to keep sufficient funds to redeem the notes as required, the banks made a tidy profit by lending out part of the funds represented by their note issues.

Allan's Commissariat Currency Notes

On 25 July, 1813, Deputy Commissary General Allan became the head of the New South Wales colony's Commissariat. He suspended the previous system of issuing store receipts and replaced then with private promissory notes.

Pre-printed in fixed sums, these new notes were, in fact, currency notes. They were issued over a period of 20 months until, on 24 March, 1815, Governor Macquarie ordered their recall and banned further issues. Allan, it appears, had been dishonestly utilising the notes for his own personal expenditure. The previous 'store receipts' system was quickly reinstated.

Allan's notes were printed in the offices of the Sydney Gazette. Records of the total number of notes issued, if they existed, have not been found. Reports from the period indicate that after the recall, notes with a total value of somewhere between £7,000 and £10,000 remained unredeemed - a huge sum for those times. In Macquarie's words, 'in the two years of Dep. Comm. Gen. Allan's issue of his private notes very bad consequences resulted and, if perservered with in that time, would have proved ruinous to both the Crown and Individuals'.

It appears that the administration was slow to learn from its mistakes. Four years later, Allan's replacement - Drennan - would again rort the system.

Commissariat Bills of Exchange

As the colony of New South Wales grew, a need to transfer money over the large distances between settlements led to the introduction of Commissariat Bills of Exchange. These bills were drawn against the issuing Commissariat office, not the English Treasury.

Pre-printed and issued in duplicate, they could be converted to Sterling only at the destination Commissariat office, ten days after presentation. To preserve security, both copies had to be presented.

The words on the bill stated:

Ten days after sight of this first Exchange, Second of the same tenor and date not paid, please pay to .... or Order, the sum of .... Sterling, value received.

The words 'or order' made the bills transferable, and thus capable of being used as a negotiable medium of exchange.

Commissariat Store Receipts

Store receipts were issued by the Government Store - the Commissariat - for local goods and produce. They were originally meant to be an acknowledgement of delivery until payment was completed by means of a Bill of Exchange on the English Treasury. The intention was that producers would accumulate their receipts over a period of time and then consolidate them for a single Treasury Bill at set times.

The wording on the receipts - payment to Order or Bearer - made them negotiable. It was not long before they were being used as transferable notes - mediums of exchange.

Four pre-printed types of receipt were issued by the Commissary. The first two were general forms used for all types of goods or produce received into the Government Store. The second two were specifically printed with the type of produce - Wheat and Fresh Meat.

Drennan's Commissariat Currency Notes

Deputy Commissary General Frederick Drennan arrived in Sydney Town aboard the Globe on 5 February, 1819, to replace the disgraced previous head of the commissary - Deputy Commissary General Allan.

Despite a lack of written authority from the English authorities, Drennan immediately advised Governor Macquarie that he was authorised to replace the store receipts system then in use. Macquarie must have been convinced because on 8 February, he promulgated a change so that 'Promissory Notes on account of the Public Service' were to be given in payment of 'Untransferable Store Receipts'. The new form of store receipt was specifically excluded from being used as a negotiable instrument - it could not be considered as a cash voucher and was not saleable or transferable. Later, proceedings were to show that Drennan had no such authority.

Drennan used the facilities of the Sydney Gazette to produce both the non-transferable store receipts and the new Promissory Notes. The receipts were printed four to a page and distributed to each of the Commisariat offices.

The Promissary Notes, currency notes in fact as they had pre-printed values of 10 pounds, 5 pounds, 10 shillings and 5 shillings, were held in Sydney. Initially, Drennan insisted that consolidation of the now non-negotiable receipts must be carried out at the Sydney office. Protests from remotely located settlers soon forced Drennan to send his officers on regular visits to the outlying Commissariats of the colony specifically to consolidate receipts for the new currency notes. These visits did not extend to Van Diemen's Land where Lieutenant Governor Sorell, with Macquarie's support, quickly fixed the problem by reverting once more to the old and well understood store receipts system.

It was soon discovered that the four denominations of currency note were easily forged. After only a short print run totalling around £500-£600, the notes were quickly recalled and destroyed.

A second issue of 10, 5, 2 and 1 pound notes replaced the withdrawn notes, printed on Drennan's 'official press' using a plate engraved by Clayton. The notes were cut and stitched into books of 100 prior to dating and signing.

Drennan's system would probably have worked, were it not for a complete lack of checks and balances over the handling of both the store receipts and the currency notes. Uncounted quantities of blank store receipts were delivered to Commissariat Offices, currency notes in reasonable condition were re-issued after consolidation for Treasury Bills, and, almost unbelievably, no record was kept of those currency notes that were re-issued, nor those that were destroyed.

Compounding the problem was a series of note thefts from the outlying Commissariats. The system was abolished in June, 1820, and once again, the old system of transferable store receipts was revived, this time with a few safegards against theft and forgery.

Drennan, with his credibility in tatters, was removed from office, arrested and sent back to England. Investigations revealed a shortfall of approximately £6,000 - a huge sum for the time.

Paymasters' Notes & Bills

In the early decades of the New South Wales colony, to pay for the goods and produce obtained locally, and to pay the soldiers, the military issued Paymasters' notes and bills. Between 1798 and 1808, promissory notes and bills were issued by the officer in charge of each military unit. Similar notes were also issued by the commanders of naval supply vessels which visited the colony. The miliatary notes were consolidated regularly for Treasury Bills while the naval issues were consolidated for Bills of Exchange on the Commissioners for Victualling His Majesty's Navy.

The system was changed in late 1808. All previously issued military notes were recalled and consolidated, and the issue of new notes was restricted to the Committee of Paymastership of the Corps. The old system continued to be used in remote locations such as Newcastle.

Under the new arrangements, two types of notes were issued. Variable (broken value) notes were used to pay for general regimental supplies while the soldiers were paid monthly in fixed value currency notes. Consolidation for Treasury Bills, Bills on the Regiment's London Agent or specie (when available) occured quarterly.

Police Fund Notes

In 1810, Governor Macquarie created the Colonial Police Fund to provide a facility from which government instrumentalities and projects could pay expenses and into which duties, fines and fees could be paid.

The money paid into the Police Fund was, at that time, the main source of revenue for the running of the non-penal facilities of the colony. The money was derived from duties on various goods including rum (spirits and wine), coal, cedar, sandalwood, oil, etc, and from licenses, quit rent , fines and fees. The Fund helped pay expenses for the gaol, police establishments, wharves, quays, bridges and roadbuilding and repair within Sydney Town.

Hand written bills drawn on the Police Fund were used regularly in payment for public expenditure.

Despite government regulations forbidding it, these notes are known to have passed into circulation. An example at right shows a Bill of Hand dated October 16th, 1813, instructing the Police Fund to pay James Bowler, Sydney, £3-5-0 for repair of pumping equipment at Government House and Barrack Square.

Two Police Fund currency note printings were made by George Howe at the Sydney Gazette from late 1814. The first was for values of £2 and £1, one of each per sheet. Their issue is unconfirmed. The second, in late 1816 through into 1817, was for values of £1, 10/-, 5/- and 2/6. Again, two different value notes were printed per page - the two lower denominations together, and the two higher ones together. The notes were assembled in stitched books containing about 100 pages. When needed, a note was cut from the book through the ornamentation on the left side, producing a circulating note approximately 140mm x 80mm in size. To reduce the incidence of forgery, the reverse side of the later notes bear a Latin extract from Cicero.

Treasury Bills of Exchange

Bills of Exchange on the English Treasury were issued by the colonial authorities to pay for the goods and produce needed to keep the settlement going.

These notes were usually pre-printed with space reserved for details such as the payee, amount, date and signature to be hand-written as required.

The wording of these bills - pay to the order of - made them negotiable, and therefore capable of being used as a transferable medium of exchange.

It was not appropriate to draw up a Bills on the Treasury for small day-to-day transactions. Instead, the Government Store - the Commissariat - used a system of transferable Store Receipts as an intermediate step. A number of these store receipts would then be consolidated, at intervals set down by the authorities, for a Bill on the English Treasury.

A similar arrangement was used by the military. Paymasters' currency notes and bills were used to pay the soldiers and to obtain local supplies. These were later consolidated, usually quarterly, for Bills of Exchange on the Treasury.

Despite the failure of two previous attempts to introduce Commissariat Currency Notes (see the Allan and Drennan issues), another attempt was made in 1826.

The first issue of these new notes, bearing the signature of Deputy Commissary General Wemyss, commenced with 500 £10 notes dated 20 September. A further 250 £5 notes were issued with the date 11 October, 1826. Additional £5, £2 and £1 notes were printed but were apparently not issued.

By this time, a steady flow of English coinage was reaching the colony. The need to utilise small denomination prommissory/currency notes dwindled and their issue by the Commissariat was stopped. With the exception of a small number of £10 notes, the entire issue, and the plates used to print them, were destroyed on 17 June, 1828.